Top Real Estate Issues Tackled By Fla. Lawmakers In 2024

Real estate matters remained a high priority for the Florida Legislature during its 2024 session, which wrapped up Friday with lawmakers making revisions to a landmark housing bill, imposing statewide vacation rental regulations, and taking further steps to shore up condominiums and community associations.

Here’s a look at some of the most notable changes lawmakers sent to Gov. Ron DeSantis’ desk — and one they didn’t.

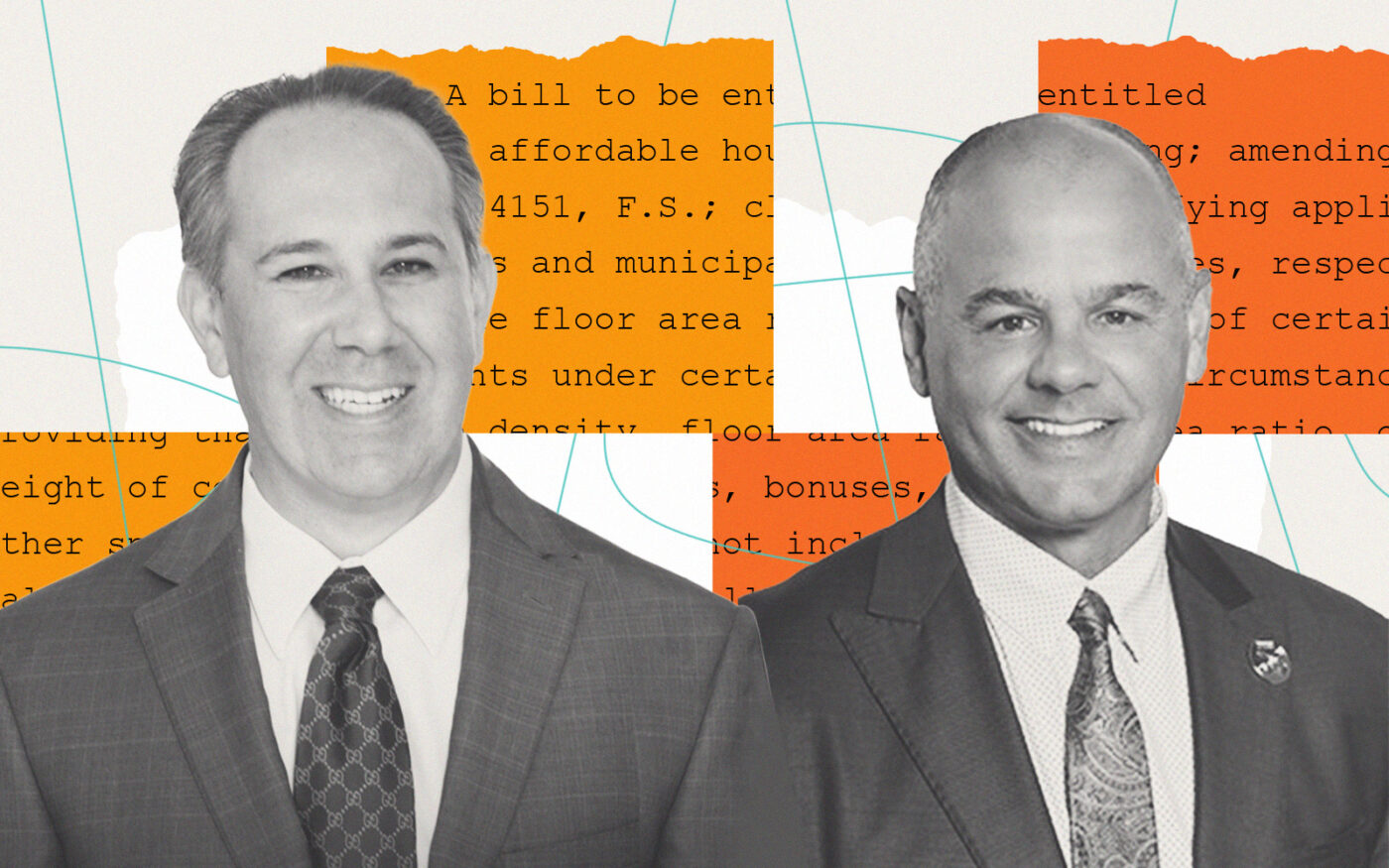

Live Local Revisions

Arguably the signature piece of the 2023 session, the Live Local Act caught the attention of real estate developers with tax breaks, building-size bonuses, and the opening of commercial and industrial zoned sites for residential projects in exchange for including affordable and workforce units. But some local governments balked at preemptions of their approval powers, even enacting development moratoriums in response.

When the 2024 session opened in January, Senate Bill 328 looked like it might temper some of those concerns, but the final version that passed appears to do more to clear obstacles to Live Local projects by adding another preemption for floor area ratio, or FAR, which determines buildable square footage, and by reducing parking minimum requirements, while curbing allowed heights only in single-family neighborhoods.

Bill Sklar, a shareholder at Carlton Fields, said Senate leadership made clear to him they did not view S.B. 328 as a “glitch bill” aimed at fixing problems, but instead the first of what is likely to be a series of refinements to the Live Local Act over several years.

Keith Poliakoff, a partner at Government Law Group, also predicted further changes — and tensions.

“While this law attempts to clarify many aspects of the Live Local Act, municipalities are already crafting ways to thwart its effectiveness,” he said. “As a result, there is no doubt that this act will once again be amended next year.”

Vacation Rentals

After more than a decade of unsuccessful attempts, the Legislature passed a bill setting a statewide framework for vacation rentals, which number in the tens of thousands in the state and have become the scourge of some neighborhoods. Indicative of the measure’s controversial nature, S.B. 280 passed by narrow margins, 60-51 in the House and 23-16 in the Senate.

The law empowers the state to license vacation rentals and regulate “advertising platform[s]” such as Airbnb and VRBO, but it does allow local governments to require registration of vacation rentals, set reasonable registration fees and inspect rentals for code compliance. Local governments can also issue fines of up to $500 and suspend rental registrations for violations, but only after multiple violations within set amounts of time and after giving the owner 15 days to resolve the violation.

The new law maintains a “grandfathering” of local restrictions that predate 2011, when the Legislature preempted local regulations prohibiting or restricting the use of vacation rentals. The new law extended the “grandfather” clause to 2016, which amounted to a carveout for policies in Broward and Flagler counties, according to a legislative staff analysis, but the Senate did not pass a last-minute amendment to “grandfather” local regulations passed by June 1, 2024.

The law also sets requirements for advertising platforms to collect and remit taxes and sets occupancy limits for rentals.

Coastal Building Demolitions

The Resiliency and Safe Structures Act, which limits local control over the demolition and replacement of certain coastal buildings, represented another controversial initiative that crossed the finish line after previously falling short.

Opponents said S.B. 1526, which applies to buildings that are deemed unsafe and don’t conform to current National Flood Insurance Program elevation requirements, caters to developer interests and threatens the character of several historic coastal communities, including Miami Beach. But while such criticism killed a similar proposal last year, this time a similar set of carveouts added during the session built momentum and led to passage by 36-2 in the Senate and 86-29 in the House.

Government Law Group’s Poliakoff said that in the wake of more stringent flood plain management requirements, the inability to rehabilitate older structures up to those standards has left numerous coastal buildings vacant and turned them into a blight on the surrounding community.

“Some local governments are so concerned with maintaining community character that they have created major obstacles in getting these obsolete buildings reconstructed,” he said. “This law eliminates the politics by requiring local governments to approve demolition plans for these impacted buildings” and new projects up to maximum allowed heights.

Condos and Community Associations

The Legislature has been scrutinizing condominiums and community associations since the 2021 partial collapse of the Champlain Towers South condo in Surfside, which killed 98 people, and the 2022 arrests of current and former board members at the Hammocks Community Association near Miami over an alleged $2.4 million dollar fraud scheme.

Lawmakers’ latest work on these issues and others related to condominiums and community associations ended up largely combined this year in S.B. 1021, which passed unanimously in both chambers.

Among its many parts, the 154-page bill requires condo associations with 25 or more units to make certain records available on a website or mobile app, mandates the maintenance of additional accounting records, and establishes criminal penalties for willful failure to comply and destruction of records.

It also adds conflict of interest disclosure requirements related to the hiring of community association managers and bids for other services, and it provides additional criminal penalties for board members accepting kickbacks or interfering with elections.

“I guess after investigating what happened with the Hammocks, they realized that there’s a lot of shortcomings in protections for the homeowners,” said Kevin Koushel, a partner at Bilzin Sumberg Baena Price & Axelrod LLP, but he added these new requirements and penalties could have a chilling effect on finding residents willing to volunteer for association boards.

Following up on building safety reforms made in 2022’s S.B. 4D and last year’s S.B. 154, the Legislature added a requirement for board member education on the milestone structural inspections and reserve requirements established in those previous bills. S.B. 1021 also exempts four-family dwellings of three or fewer stories above ground from having to undergo the new milestone inspections.

But lawmakers notably did not extend the inspection deadlines at the end of 2024 for condos to complete their milestone inspections or take any steps to provide financing programs or assistance for condos.

“I think there was some hope, at least from a lot of the condo associations, that the deadlines would be extended or some additional ability to sign contracts and have the work deferred,” Koushel said.

“I wish they did, but they didn’t,” Carlton Fields’ Sklar said of the potential for financing help, but he said House Speaker Paul Renner, R-Palm Coast, felt strongly they “were not going to kick the can down the road” on the inspection and reserve requirements.

Lawmakers also rolled in proposals from two other bills to update definitions in the Condo Act to acknowledge the creation of condominiums within multi-use or multi-parcel projects, which is relevant to the growing trend of branded residences in condo-hotel and other mixed-use projects.

Additional provisions require clear declarations of how costs and control of those projects will be apportioned with these partial condos, and they mandate disclosures of these agreements for new and resale transactions of units.

“Those are, in my estimation, significant consumer protections that did not previously exist,” Sklar said.

Foreign Ownership Limits

One of the Legislature’s actions that drew the most attention in 2023 was the passage of S.B. 264, which severely limited land and real estate investment by people and interests tied to the People’s Republic of China and six other “foreign countries of concern.”

The Republican-controlled Legislature delivered on a top priority of DeSantis ahead of his ill-fated presidential run despite considerable controversy and questions about the law’s clarity. Some investors, especially private equity funds, have expressed concerns that noncontrolling members of a fund would be restricted individuals under the law.

Lawmakers looked into providing more clarity on certain parts of the law and potentially loosening some of the restrictions on Chinese individuals in S.B. 814, but DeSantis made clear during a press event that he opposed any backtracking, and ultimately no changes were made — leaving some attorneys and their fund clients looking for more.

“A lot of us are hoping that the administrative side, the bureaucratic side that’s making the rules and interpreting the rules can clarify that and maybe put out guidance that stresses that squarely enough that people will feel comfortable,” said Joe Hernandez, a partner at Bilzin Sumberg, who noted the firm has received calls since the law’s enactment from concerned fund clients.

–Editing by Haylee Pearl and Philip Shea.

Article Link: Top Real Estate Issues Tackled By Fla. Lawmakers In 2024

Author: Nathan Hale